From Shamrock Rovers to the NFL: the tale of Neil O’Donoghue

Neil O’Donoghue was 17 years old when he was working as a ticket collector in Heuston station, Dublin, while playing part-time for Shamrock Rovers. Never much of a student, prospects were few and far between for him and Ireland seemed small and suffocating. He had already worked as a labourer in London when one day, he was approached by his brother’s friend, who asked him if he was interested in a scholarship to the US. O’Donoghue decided to chance his arm. “My idea was to come over here for a year and have a good time,” he says. “As it turned out, I fell in love with the place.”

Auburn University lies on the eastern border of Alabama and has a history rooted in American football. O’Donoghue, now 63, had never played the game before – in fact, he had only been to one match in his life – but he was determined to earn himself a full scholarship and stay in the States. He had been studying PE and playing football for Saint Bernard college but he became tired of his part-time job – cleaning trucks with acid – and when the price of petrol rose, Saint Bernard dropped the football, forcing O’Donoghue to look elsewhere.

He decided that he could transfer his kicking skills from one football pitch to another and so he made the 163-mile journey to Auburn. “I drove down with a couple of buddies and knocked on the coach’s door. I was sticking my neck out but I didn’t know any better. I thought I had the ability to do it.” He was right.

With the end of the summer comes the start of the NFL season and although O’Donoghue is still a fan of the sport, his past as a player is behind him – and that is where he likes to keep it. Unlike many former professionals, he tends to avoid club functions and does not mix with former team-mates. “When I left it, I left it – you got to leave that behind you,” he says. O’Donoghue, the last Irishman to play in the NFL, also rarely does interviews, despite having a story as action-packed as that of any former NFL player.

Liston Eddins, the Auburn captain, was working out when he saw the head coach, Ralph Jordan, enter the field on a winter morning with O’Donoghue. “How can this tall guy possibly kick,” Eddins thought to himself. He was soon to find out. “They started from about the 30-yard line,” Eddins adds: “and good God it goes so high and so far over the bar that coach Jordan motions him to back up 10 yards. He gets to the 40 and kicks two, and they clear the posts by a long way. Coach Jordan backed him up again and it goes through by a good 15 yards.”

The trial was enough to convince Jordan of O’Donoghue’s skills and earn him the full scholarship. That one game O’Donoghue had watched was between Auburn and the University of Alabama. A year later he would be playing in that game in front of 60,000 people. Within two years of his transferring to Auburn, he would be a fifth-round draft for the Buffalo Bills.

The step up from college to the NFL is one many players fail to come to terms with and O’Donoghue was not ready for it. “What the f*** am I doing here?” he thought upon entering the Bills’ locker room for the first time and seeing players such as OJ Simpson. O’Donoghue was also not ready for his ill-tempered coach, Jim Ringo, who, for this six weeks there mistaken called him Phil – Ringo was muddling his name up with that of the television personality Phil Donahue. During one team meeting, O’Donoghue remembers Ringo sending chairs into orbit, while that coach welcomed him to his first game by bawling him out in front of his team-mates for wearing jeans and flip-flops.

After some lopsided performances, O’Donoghue was cut after five games and a game-winning field goal that snapped a 14-game losing streak for the Bills. At the time, one anonymous coach was quoted as saying: “Neil’s head just wasn’t suited to the NFL.” O’Donoghue agrees. “When you become a professional you are fair game for everybody. There is no holding back, you don’t get a free pass … I’d had my fill of it.”

The cut hit O’Donoghue hard and he was contemplating “getting a real job” when the call came from the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in 1978. At the Bills, he felt he had perhaps not taken his opportunity as seriously as he could have – the squad would “let loose for a couple of days” after a game – but this time he promised himself it would be different and his second season there would prove to be one of the most memorable of his career.

It began with a stark warning from the coach, John McKay. Should the Irishman falter, “we’ll bring someone else in”, he said. “Kickers are like grass, they are everywhere.” The metaphorical boot in the backside did O’Donoghue the world of good. He scored crucial kicks in wins against Baltimore, Minnesota and Detroit, and in the final game of the season, surrounded by rain and fog, he kept his nerve to kick a fourth-quarter field goal to secure the NFC Central title for Tampa.

Tampa would reach the Championship game that season – eventually losing 9-0 to the LA Rams – but O’Donoghue sat on the sidelines, a frustrated figure, unable to change the tide for his side. He was to be even more frustrated when the summer months came and McKay decided his field-goal kicking was too erratic and cut him.

As with his time at Buffalo, O’Donoghue felt he’d had enough. “There was a lot of pressure doing what I was doing. When you get out of it, it’s like the air is let out of a balloon and you take a big deep breath. It was nice to work as a normal person.” That work was on building sites, constructing condos. It was on 10th floor of one such high-rise that he was told St Louis Cardinals were interested in him. “That was on a Monday and I was playing that next Sunday against Washington … but there was a lot that happened in between.

“I went up there on a Tuesday night and the head coach, Jim Hanifan, says: ‘What we are going to do after practice tomorrow is have you and the kicker [Steve Little]and we’re going to have a kick-off. Whoever wins is going to get the job.’” Little was a first-round draft with a sparkling college record but he was struggling in the NFL. With the entire team and coaching staff looking on, they were put through their paces. From 25 yards, he made nine of his 16 attempts. O’Donoghue made 14.

The next morning O’Donoghue got a call from Hanifan. He was in. O’Donoghue made his way to practice and bumped into Little, who offered to take him out for a drink that night. O’Donoghue politely declined. He felt his kicking was a bit rusty and there was the game on Sunday. “The next morning I wake up and turn the TV on and there was this horrific car accident. It turned out it was Steve.” Little would spend the rest of his life as a quadriplegic.

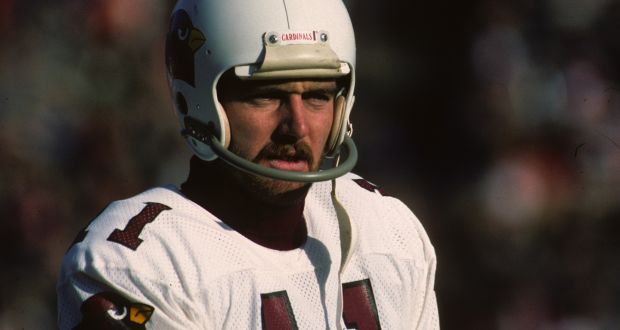

O’Donoghue’s time at the Cardinals was a bumpy one. He is best remembered for missing three field-goal opportunities in one match in overtime – including one from only 19 yards – and then there was a kick against Washington. It came at the end of a record season for him and was a game the Cardinals had to win if they were to make the play-offs.

He had recorded a career-high 108 points before that match. He added three more extra points and two field goals to bring his tally to a then franchise record of 117. “My expectation was that they were going to throw the ball out on second down and stop the clock,” he says. “Instead, they went for a play and the ball was caught inbound with the clock ticking.” Players entered and exited the field in a hurry. Confusion reigned and O’Donoghue did not have time to set up properly. He missed and St Louis’s play-off dreams were shattered. “That’s the way it goes,” he says.

He would play one more season before being cut after missing three attempts during a defeat by the Houston Oilers. “The thing that I’ll always remember about Neil O’Donoghue was the unique attitude that he displayed,” Hanifan said at the time. “Neil battled through adversity on several occasions. I wish him good success,” added Hanifan – but there would be no more on-field success. O’Donoghue had enough and decided to retire.

He moved back to Clearwater, Florida, to his wife and kids and a more normal life. He worked once more in property (he had earned his real estate licence as a player) before moving into insurance and then on to cars, a job he has been doing for more than 20 years. It’s in sales. “You don’t take it home with you,” he says, with obvious enjoyment. “I did it for 10 years and succeeded at everything I wanted to do,” he says. “I wasn’t the best guy in there but I hung in there and I can walk away and say I did something.”