Big Chief

Auriole Fountaine investigates the enigma of Francis O’Neill: the police chief who saved Irish music.

“ In any Irish city or town, you see statues of various people, yet very few of them come close to achieving what Chief O’Neill did. He’s never had official State recognition.”– Harry Bradshaw, expert in traditional Irish music.

So who was Francis O’Neill and why is it that he is one of Ireland’s greatest unsung heroes?

The life of Francis O’Neill and the legacy he left behind is as remarkable as it is inspirational. Born in Irish speaking West Cork in 1848 into a musical family where he spent his days playing the flute, his childhood and his love for Irish music and culture laid the foundation for the man he would become.

While Ireland was still in the grip of a devastating potato famine, the spirited young Irishman ran away from home when he was only 16. First working as a cabin boy on an English merchant vessel, he was married at 22 in Illinois before moving to Chicago where his extraordinary life began in earnest.

Harry Bradshaw has given lectures on O’Neill to American students at Trinity College Dublin. He also masterminded the traditional music centre at Chief O’Neills hotel in Dublin, which was intended to offer tourists and locals the opportunity to experience the joy of Irish ‘trad’.

“His life is an amazing story, like a novel. He married at 22, but by that time he’d educated himself, seen the greater part of the world and had a lot of life experience behind him,” says Bradshaw. O’Neill was noted for his intelligence and integrity but should really go down in history as the police chief who saved Irish music. Indeed he was to become the foremost collector of Irish traditional music in the latter third of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th.

His notoriety began as early as 1873 when he signed on as a policeman in Chicago, then the second largest city in North America, not to mention the most violent. Within a month of enrolling O’Neill was shot while tackling an armed burglar. The bullet, which was considered too dangerous to remove, remained in his spine for the rest of his life. In later years he was shot again, this time in the hand. It was a dangerous era to be policing the mean streets of Chicago, which has gained infamy for its connection to Al Capone and the violent mobsters of the 1920s.

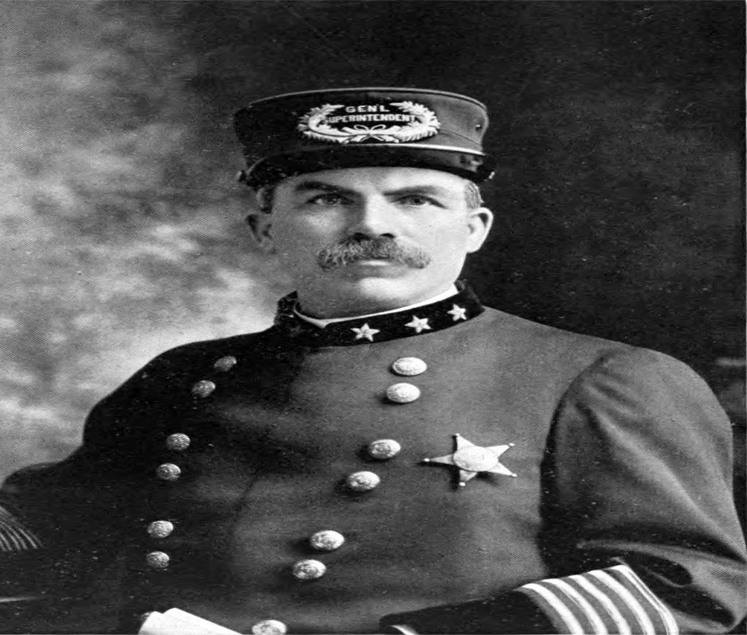

Nicholas Carolan is director of the Irish Traditional music Archive in Dublin and author of A Harvest Saved, a book on O’Neill’s life. He told Garda Journal: “He began as a policeman on the beat, and rose through the ranks to become General Superintendent over 30 years.

He was noted for his administrative abilities. He had a range of skills rare in the Chicago police. He was an honest and neutral policeman, not associated with any political camp.”

The proportion of Irish in the Chicago police was high, as being a police officer was one of the standard ways the Irish could advance themselves. O’Neill was to be singled out for his integrity. While many of the Chicago police were known for being corrupt, he came to the attention of the police board through his outstanding character and his steady advance through the ranks began.

Harry Bradshaw believes the turning point in O’Neills career came in 1890 when he was made Lieutenant. “It was a major step because at that time there were many Irish on the force, but because they came over as emigrants, they ended up as footsloggers. They made up the rank and file, but not the brains of the police force. These avenues were closed off to emigrants.”

Bradshaw is convinced it was O’Neill’s ability and bravery which saw him gain such authority in 1890. Four years later his brawn helped him win first place in the state exam for rank of Captain. Only six years later O’Neill was made Chief of Police. Nicholas Carolan believes the characteristic which set him apart was his fearlessness and the fact that he led by example.

“He was honest, conscientious and able. The needs that the public have of their police don’t change from century to century. He sacked anyone found guilty of taking corrupt payments. He dismissed a number of detectives, anyone who didn’t have a clean hand.”

“Ninety nine out of 100 policemen in Ireland will never have heard of O’Neill and yet against all the odds, he obtained the highest rank in the police in the second city of America, in an era of very little opportunity,” says Bradshaw. While O’Neill’s rise to Chief of Police was nothing short of remarkable, it was in Irish music that he was to leave his mark. His working life was spent on the force, but O’Neill’s life’s work, and his lifelong love, was Irish music. He began the mammoth task of collecting Irish tunes to preserve the lively jigs and haunting melodies of his homeland. At this time Chicago had a better tradition of Irish traditional music than any spot in Ireland. This was because musicians from all the 32 counties in Ireland resided in the city, and he was able to collect what Carolan has called, “The largest snapshot ever taken of Irish traditional music.”

O’Neill became obsessed with keeping Irish music alive at a time (before the revival in the 1950s) when he felt the Irish in both Ireland and Chicago were turning their backs on their culture. Peter Browne is the commissioning editor of music programmes for RTE Radio 1 and an accomplished musician himself. He says people were still turning their backs on their music when he was growing up in Dublin.

“When I was learning music, it was scarcely heard in the city at all; there were only two places where it could be found. It was essential for the elderly in the country. There was a post-colonial sense of shame of not playing it. It represented to people where they had come from rather than where they were going.”

This view is reiterated by Harry Bradshaw, who says before the great Irish music ‘renaissance’ many people felt it was, “music linked to a language which identifies us with the bad times.” With reference to the colonial period, and also some elements of the church, O’Neill himself said, “Traditional Irish music could have survived even the famine if it had not been capriciously and arbitrarily prescribed and suppressed.”

With the revival of traditional music in the 1950s O’Neill’s collection was the source for a new awakening. In numerical terms he collected around 3,500 traditional Irish tunes in eight books which he had drawn from all possible sources; printed material, manuscripts, but chiefly from living musicians. O’Neill himself would listen to the tunes and his assistant James O’Neill, from County Down, would transcribe them. The police chief was blessed with what must have been a photographic memory. After hearing a tune only once he could remember it perfectly.

However, it was not just O’Neill’s ear for a melody that was remarkable, but his forward thinking. “He had the foresight to see that with the great exodus of people, that among these people fleeing Ireland must have been many musicians who carried their folk music with them and knew they would have no chance of making it back and their music would die with them,” says Bradshaw.

O’Neill therefore began to photograph musicians, and ahead of his time recognised the importance sound recording would have in the presentation of Irish music. The earliest recordings we have of Irish folk music are down to his private mission to record these tunes in the days before electronic recording or CD’s existed, using a cylinder machine in 1902; the state of the art recording technology of the day, only patented in 1872. One of the principal reasons why O’Neill’s collection should be prized above all others is because the music he gathered was entirely faithful.

He was a traditional Irish musician writing for other traditional musicians. While it is true that other collections were published, they failed to make their way into the hands of other musicians like O’Neills did. He became Ireland’s principal source of music and helped boost literacy among his peers.

Decades after he retired, his name was synonymous with what makes a good Chief of Police. Nicholas Carolan states: “He made a clear distinction between his police life and music life. When acting as a policeman, he was decisive and tough. In his private life he was quiet, modest and dedicated to his family. Music was his private obsession throughout.”

Two of O’Neill’s books include Irish Folk Music: A Fascinating Hobby, with some accounts of fascinating hobbies from 1910 and Irish Minstrels and Musicians with Numerous Dissertations on Relative Subjects, or simply, The Story of Irish Music from 1913.

“He had a range of skills rare in the Chicago police. He was an honest and neutral policeman, not associated with any political camp.”

The latter gives 480 pages of enthralling information about the lives of Irish musicians, documenting their existence through a combination of music and humour. Of the musician ‘Mrs Kenny’ O’Neill writes: “Devotion to art does not appear to have unfavourably affected the size of Mrs Kenny’s family for we are informed she is the prolific mother of 14 children!”

O’Neill’s life was not without tragedy. As the father of 10 children he lived to see one daughter and all of his five sons die, three of them on the same day from diphtheria. Perhaps O’Neill’s most famous publication 1001 Gems, The Dance Music of Ireland, O’Neill’s 1001 Traditional Irish Tunes was dedicated to his son Roger, who he said was “the first member of the Irish Music Club called by the great leader to join the heavenly choir.” It has never been surpassed as the standard reference for traditional Irish musicians.

Another tragedy in O’Neill’s life was his disillusionment and belief that his work had been in vain and was not appreciated by his compatriots. He never made money from his efforts; it was done for the love of his home country and its traditions. From 1904 onwards O’Neill stopped playing music altogether and sadly he died in 1936 before he could see the revival of Irish music and reap the rewards of the seeds he had sown. While O’Neill is recognised in Irish music circles, he remains largely unknown.

Even the Dublin hotel named in his honour has scaled back on the Chief O’Neill theme which once permeated the complex. There is an O’Neill mural, and a small sculpture, but gone is the Ceol museum, where Irish dancers and musicians once performed every night of the week. Nor can you purchase O’Neill memorabilia in the giftshop.

Pat Hevey is General Manager of Chief O’Neills Hotel and has noticed the ignorance towards O’Neill which exists in his homeland.

“I’ve never met a real Irish person who knew who he was,” he says. He describes the Ceol centre as “really something.” But the £750,000 invested in the centre wasn’t enough to draw the crowds and it folded in November 2001.

Although the revival brought with it an awakening of interest in Irish music and a realisation among the Irish of the value of their culture, it was too late for O’Neill to see. While he is forgotten outside of music circles, he has immortalised Irish musicians and their work for all time. The Riverdance phenomenon, which has taken the world by storm, owes as much to its talented dancers as it does to O’Neill’s tunes.

“He did ensure that thousands of reels, jigs and hornpipes survived into the 20th century. When the revival came in the 1950s, the fact that all this music had been collected and preserved in print and was just waiting to be discovered by music practitioners was a real bonus. If he hadn’t done his work, those tunes would’ve died,” says Harry Bradshaw.

Most Irish people don’t know who Chief O’Neill was, but his music is still practised and played today. He may be dead but his legacy lives on; a policeman and musician for Ireland to be proud of.